Abstract

Keywords:

Identity, Mental Health, Wellbeing, Post-traumatic Stress, Transition.

Introduction

When someone thinks about a military veteran, they might think of the older person selling poppies in the local supermarket or Highstreet. Maybe they think of Captain Tom Parker or the Remembrance Day Parade. The veteran community are visible at events such as these, and other significant anniversaries but is not very visible outside of these types of events. The fact is though that you have probably passed a veteran, or two in the street today. According to the Royal British Legion Survey RBL (2014) veterans account for 4.4% of the UK population, therefore veterans represent a significant community of ex-military personnel. The term community is used because as Balfour (2018) explains, there is some evidence to suggest that ex-military personnel continue to connect remotely with their peers via closed and specific social media sites like Facebook and that these virtual networks operate as a quasi-support environment (p 562). Brewin (2011) cited by Balfour (2018) argues that military service can lead to profound changes in identity, affecting both military personnel’s perception of themselves and the world. This change of identity has been termed transition by several authors including Ahern et al. (2015); Binks and Cambridge (2018), Cooper et al. (2018) and Lancaster et al. (2018).

During military service, the individual may experience and endure extreme hostile environments, be in situations that can result in life-changing injury to themselves or others and violent death of comrades and civilians. They may have to deal with the aftermath of these incidents and are expected to conduct themselves professionally. This inevitably takes its toll on the individual and can result in moral injury, posttraumatic stress (PTS), and other mental health issues. At the end of military service for some, the transition back to civilian life is a complicated, frustrating, and difficult one. As Ahern et al. (2015) describe normal life is alien, many veterans feel a lack of purpose in civilian life, it lacks structure, and they feel a disconnection from people at home.

It would be rational to assume that community music (CM) projects with this community would be a helpful intervention to alleviate some of the issues that veterans have in adjusting to and dealing with life in a civilian community. Communal music making has been shown to have positive effects on feelings of detachment and negative beliefs about oneself (Landis-Shack et al., 2017), it provides a means for people to define and redefine their self-identity (Baker & Ballantyne, 2013), and group songwriting experiences have been used to develop socialization skills or engender feelings of belonging to a community (Bradt et al., 2019). Landis-Shack et al. (2017) also cite (Carr et al. 2011) and explain that music can help ground someone in the present moment when faced with an intrusive or distressing reminder, such intrusive throughs are symptomatic of PTS. The UK veteran community, however, is a population group that is underrepresented in community music projects and research. (Balfour, 2018), in the Oxford Handbook of Community Music, states that “Despite some high-profile music projects such as military wives, in the United Kingdom, there is very little ongoing work exploring the relationship between music and the needs of military audiences (p558).” At the Forces in Mind Trust, Research conference in March 2022, presenters from all parts of the UK shared the research and projects that were being conducted in their region. There were reports of intervention projects and research including a variety of artistic activities, but there were no reports on any music projects taking place.

Previous research has found that there are studies of CM interventions in non-veteran communities that study similar mental health conditions and issues that the UK veteran community have, and there are studies that have been conducted with non-UK veterans suffering from PTS, Noyes and Schlesinger (2017), for example, stated that early studies indicate that music therapy results in alleviation of PTS symptoms (p81). So why does it appear that there are very few studies or projects involving music and the UK veteran community?

Could it be that there is a lack of engagement on the part of the veterans, Balfour (2018) states ‘there is an in-built resistance between military personnel and civilians instilled from day one of boot camp. Civilians are different. You only trust each other. The military is your family.’ (p537). This could be the reason for what Balfour (2018) describes as the distrust and suspiciousness that the veteran community have for artists and university researchers, or could it be that the good intentions that community musicians have when trying to work with veterans are not welcome and the Illich (1968) presentation ‘To Hell with Good Intensions’ cited by Balfour (2018) should be observed and the community left alone?

This research will hopefully extend the limited research on the effects of CM on the military veteran community and whether there is value in attempts to engage the veteran community in CM interventions. The potential practical implications for this are for readers and funders to advocate future funding to promote opportunities for music-making projects in the veteran community. This study intends to assess the viability of long-term funded projects and the creation of music clubs that local military veterans can access to engage in music activities to promote and enhance wellbeing. The topic of the study will be to examine the potential impact of CM on the UK veteran community and the conditions required to sustain and develop veterans' music activities.

The key questions of this study will respond to how community musicians can engage the veteran community in active music-making to promote wellbeing, to help readers, understand the impact of military life on an individual and how the development of a musical identity can assist in providing a new social place for the veteran.

Therefore, the research questions are as follows:

1. Can participatory group music-making have a significant positive effect on the well-being of UK military veterans?

2. Could the development of musical identity provide a new social place for veterans through a community music intervention?

3. To what extent could the military veteran use active music-making to assist in the regulation of emotions and positive mental health?

To do this the veteran community must be put into context and the military & veteran identity understood. Current and relevant research involving veterans and music will be examined and the principles of community music outlined. The study will engage with newly formed veteran music groups and using these groups as case studies will explore how these groups have developed, the barriers they have encountered and the experiences of the organisers, facilitators, and participants. The findings from the observation of practice and the qualitative data collected from participants exploring both its practical and emotional impact will inform future research to guide an action-based research project in the future.

Positionality

According to Holmes (2020), the term ‘positionality’ both describes an individual’s worldview and the position they adopt about a research task and its social and political context (p1). Bourke (2022) explains it is reasonable to expect that the researcher’s beliefs, political stance, and cultural background (gender, race, class, socioeconomic status, and educational background) are important variables that may affect the research process. Rowe (2014) states It influences both how the research is conducted, and its outcomes and results. Holmes (2020) argues that self-reflection and a reflexive approach are both a necessary prerequisite and an ongoing process for the researcher to be able to identify, construct, critique and articulate their positionality (p2). Finlay (2002), explains, that researchers can use reflexivity as part of their methodological evaluation, as a way of demonstrating trustworthiness. Being explicit about what we are bringing to the research allows those who read our work to better grasp how we produced the data. The reader should then be able to make a better-informed judgement on the research process and how truthful the research data is (Homes 2020 p3).

Caddick et al. (2017) describe tensions as a civilian researcher working with UK veterans. As an outsider, he recognised his positionality and discusses how various interested parties talk about and for veterans. He cites Baker et. al’s (2016) description of how when others talk about veterans it creates uncomfortable tensions. This is brought home with a comment from one veteran in Craddick’s’ study.

I read that academics reflect on how they can witness veterans’ lives and interact with them to better understand their experiences. In some ways I applaud you and in another, I think it's futile … I’ve spoken to other veterans there is an understood brotherhood and trust is automatic … Academics are only witnesses to only what we are prepared to tell. (Craddick et.al 2019 p108)

Muhammad et al. (2014) in their study of the impact of positionality on Community Based Participatory Research describe how their research teams would as far as possible, reflect the class and ethnicity of the communities they investigated and ‘found that matching researcher identity with that of the interviewee minimised social distance, mistrust and barriers to hidden transcripts (Hiding their true thoughts) …to increase the validity of the knowledge accessed.’

My history as a veteran with 15 years of service in the Infantry and Army Physical Training Corps, holding posts such as Deputy Head Group Therapist at the Defence Services Medical Rehabilitation Unit and Head of Rehabilitation at the Army Training Regiment, Pirbright and having treated many seriously injured military personnel leads me to I believe that I am perfectly suited, if not uniquely suited to undertake the research for this study. I also have an existing network of veteran organisations and my positionality will allow the empathy and trust of the veteran community.

As part of the veteran community, I identify very much as an insider, having similar life experiences though not exactly those same experiences as other veterans. I have what Holmes (2020) calls a ‘lived familiarity,’ and we share a common language and a sense of trust with other veterans. Merriam et al. (2010) and Muhammad et al (2014) would describe this as an ‘indigenous insider,’ someone who is from that culture or community – shares the values and beliefs and can speak with authority. In my research, this may help with the asking of more meaningful questions, the phrasing of questions and how to ask them in a veteran-sensitive way. It may allow the participants to feel more like co-researchers, to open up more and for me to interpret the answers to questions more effectively. The veterans themselves may feel that the data they offer is likely to be treated and given a voice in a more respectful way than that of a non-veteran researcher.

Methodology

Secondary Research:

This study is designed to investigate the efficacy of using CM interventions to promote well-being in UK military veterans. To do this the UK veteran community and the issues that the community and individuals within the community face must be understood. Secondary research will be reviewed through publications by organisations such as the Ministry of Defence, Office for National Statistics, and Office for Veterans Affairs to build a picture of the make-up veteran community and support organisations such as the NHS, the Royal British Legion and veteran support charities to investigate the issues veterans face and the support available for them. Military and veteran identity is examined through Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory and how the transition to military identity and veteran identity occurs. It will also investigate the legacy of military identity and the challenges the veteran encounters in the transition back into civilian society.

Observing the sparsity of empirical studies involving CM interventions with UK veterans, secondary research will also review CM as an intervention, the work of CM and music therapy interventions in the veteran communities of other nations and interventions with non-veteran groups that encounter similar issues to assess how music could be used to alleviate some of the problems veterans face. Much of the secondary research refers to the treatment of those suffering from mental health issues, mainly PTS using music therapy modalities. The benefits of mental well-being illustrated in these studies are of utmost relevance to this study.

Primary Research: Primary Research is carried out with two newly emerging veterans’ music groups. The initial concept and vision for the groups, the set-up of the groups and the barriers, encountered through set-up and development will be examined. The value of participation will be investigated through the perspective of the organiser/facilitator and that of the participant to develop an understanding of how participation in the group affects well-being and the effect that has on the individual's mental health in general.

The field site is at the NWVCoD rehearsal venue at St Helen's. The participants (n= 7). The Guitars for veterans group situated in South Wales were studied remotely and contacted by telephone, online technology, and social media. All participants were over the age of 18 and were provided with a project information sheet explaining the research, data collection and storage, they were aware that they would be given pseudonyms. Ethical approval was granted by the York St John University ethics committee.

Data Collection: The data collected included: Organiser/ facilitator questionnaires Organiser/ facilitator Audio/video recorded semi-structured interviews Participant initial questionnaires Participant reflective journals Participant Audio/video recorded semi-structured interviews Audio/video recordings of rehearsals & performances Field notes of observations of rehearsals and informal conversations. Questionnaire answers, field notes and semi-structured interview transcripts were analysed and coded using descriptive and value coding (Saldaña, 2020). Themes were identified and thematic groupings were created where corresponding texts were inserted in a spreadsheet side by side with other text in the thematic groupings.

Ex military in Context

Statistics:

According to the Office for Veterans Affairs, the UK government defines anyone who has spent at least one day in military service as a UK military veteran OVA (2020). The Ministry of Defence, cited by Stevelink et al. (2018) states there are more than 19000 regular service personnel leaving the UK armed forces each year. The Royal British Legion, Household Survey in 2014, found that there were between 6.1 to 6.2 million members of the population that were part of the ex-services, veteran community. 2.8 million (4.4% of the population) Identified as veterans themselves and there were 1 million dependent children and 2.1 million dependent adults. 64% were over 65 years of age and almost half of these were over the age of 75 (RBL, 2014). In figures released by the Ministry of Defence of a survey conducted in 2017, it was estimated there were 2.4 million UK Armed Forces Veterans in Great Britain. The majority were male (89%), predominantly white (99%), and 60% were aged 65 and over (MOD, 2019). The high numbers of ageing veterans are due to the large numbers of those who served in World War two and completed post-war National Service. There will be more substantial data about the current number of veterans in the UK when the results of the national census 2021 are released. In this census, the question was asked for the first time if a person had served in the military. According to the Office of National Statistics, the results will be released in October 2022 (ONS, 2022). However, in an article published by the MOD, these figures are expected to change as the older members of the veteran community pass away and are expected to reduce by 1 million to 1.6 million by 2028 the percentage of working age will increase from 38% to 44% and the percentage of female veterans will increase from 10% to 13% (MOD, 2019).

Military Identities

How we think about ourselves, and others are represented by the concept of identity. ‘It identifies those with whom we see ourselves as similar as well as those with whom we see ourselves as different (Brenner et al., 2021). People derive their identity or sense of self largely from the social categories to which they belong. (Stets & Burke, 2000). Brenner et al. (2021) maintain that people have many identities that exist in an ecology of identities within the self, and those identities can be enacted, altered, or abandoned in different situations. Our identities are learned through what Turino (2008) calls socialisation where we model ourselves on others that we encounter. Quinn (2021) explains, that the likelihood of playing out an identity across different situations is referred to as salience and the importance of that identity to an individual is known as prominence. An abrupt identity change may change the prominence and salience of other identities in the individual (Quinn 2021).

McKinlay and McVittie (2011) explain identity refers to the person's central being, which persists through their biological history. Personal identity is a sense of self, built up over time, it is experienced by the individual core or unique to themselves and emphasises a sense of individual autonomy (Hitlin, 2003). Stets and Burke (2000) and Quinn (2021) describe three bases of identity, (1) person identity, the unique way people see themselves, (2) role identities, the meanings associated with roles that are attached to a position in society, and (3), group or social identities, the perception of uniformity among members of a group. In identity theory, role identities are defined in part by their relationship to counter-role identities such as the father's role identity in contrast to that of the mother or child (Quinn 2021) The cognitive process of seeing oneself as a representation of a role and the norms associated with the role is termed, self – verification. This process of classifying oneself has been termed identification (Stets and Burke, 2000). In social identity theory, people see themselves as being like other group members, feel a strong attraction to the group as a whole and their perceptions and actions are at one with the group. The cognitive process of seeing themselves as a representation of the norms of the group is termed depersonalisation and the term ‘self-categorisation’ is used to describe the processes in which group identity is formed (Stets and Burke, 2000). In these group contexts, friction between insiders and outsiders of the group can occur, Hogg and Rinella (2018) describe how there can be a positive emotional bias and behavioural tendencies toward the in-group and a negative emotional bias and behavioural tendencies toward the out-group.

Woodward and Jenkings (2011) describe how the military recruiting process points to a military identity as a matter of individual determination with the possibilities of a variety of military occupations and activities. The prospect of an exciting, adventurous life may be a pull factor for a younger person and the feeling of the boredom of living with parents and a job with few prospects may be a push factor in deciding to join the military.

To be successful the recruit must undergo a transformation process that begins during initial entry as recruits learn the customs, habits, practices, norms and policies that will dictate their time of service, the initial entry process strips the recruit of their civilian life (Lancaster et al., 2018). Cooper et al. (2017) explain that transition to the military culture during basic training is nonoptional. Those that cannot accept this new military identity either leave before completion through their own discharge or will be discharged for breaches of discipline. This transformation process starts with socialisation to the military culture, and recruits are subjected to forced separation from civilian life, civilian clothes, hairstyles etc. to make way for a strong identification with military culture. (Godfrey et al., 2012). The uncertainty that the recruits experience during this phase of training causes the formation of bonds with other service members, feelings of unit cohesion and the development of a unique military identity, (Lancaster et al., 2018). Cooper et al. (2017) cite Hockey (1986) that the lack of any offstage available to recruits ensures that any sense of individuality or prior identity is removed.

As service goes on the military identity is then reinforced and in a study by (Lancaster et al., 2018) it was found that most dimensions of identity increase as the number of years and number of deployments increase. In the Binks and Cambridge (2018) study, it was found that respondents acknowledged that their military identity became their primary and dominant identity, (most salient and prominent). The possession and performance of professional military skills were fundamental to claims of military identities, such as their trained and skilled ability to use weapons and although some skills were potentially comparable to civilian skills, military attributes were emphasised such as the hostile environments in which they were performed (Woodward and Jenkings 2011). Woodward and Jenkings (2011) also explain that enactment of the skills was understood essentially as a collective group endeavour and the strong emotional bonds were noted in the study with terms such as family being used in describing their comrades. This strong sense of identity and social bonds become stronger, more salient, and prominent the longer a person serves (Woodward and Jenkings 2011). Stets and Burke (2000) observe that as this depersonalisation takes place it enhances perceptions of the stereotypes of the in-group and out-group. The in-group being members of the military and the out-group being civilians. This reinforces Balfour's (2018) statement, ‘there is an inbuilt resistance between military personnel and civilians, civilians are different. You only trust each other. The military is your family’ (p 556).

The service member does not however lose all of their civilian identity, only that the military identity becomes the most prominent and salient of the individual's many identities and they do not live wholly in a military society. Cooper et al. (2017) describe the temporary transitions that take place whilst on leave and the civilian life events such as getting married and having children and that a complex cultural transition must be navigated when moving between military and civilian environments.

Eventually, military service must come to an end. Some service members may have served a full military career and retire having completed the maximum time they are allowed to serve. Some service personnel may need to leave the forces due to injury, health, or mental health issues and for some, the greedy institution described by Cooper et al. (2017) and its demands on the individual that put service over family may come to create a push factor for the freedom from a structured lifestyle and the pull factor of family life may make civilian life more appealing. At some point, all service personnel must leave the military and negotiate the transition back to civilian society.

Military Veteran Identities

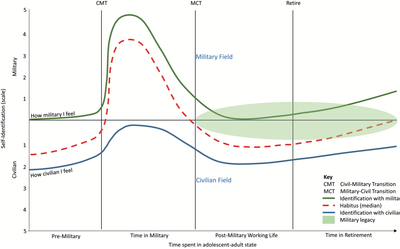

In the pre-military phase, the level of how military a person feels will increase as they consider enlisting and then rises sharply after basic training. Very quickly the person feels almost totally military, but the model acknowledges that military personnel still retain aspects of their civilian lives whilst serving. How military a person feels while serving diminishes as the time served goes on and the model illustrates that during an individual’s time in service there is a shift toward the pull of civilisation and the pull factors of returning to civilian life take hold. The model also indicates that during post-military working life elements of the military identity remain and the prominence of the military identity starts to increase once again toward the end of working life and increases further in retirement.

Integration back into civilian society at the end of military service must take place, and the military person becomes a veteran, there is a return to normal life and according to Iversen and Greenberg (2009) ‘in the UK despite the press focus on negative outcomes for war veterans, the limited existing evidence suggests that the majority do well after leaving the armed forces (p 101). This is not a simple exercise, however, and the transition back to civilian society can be as abrupt as the transition from civilian to military.

The military legacy creates problems for veterans during transition and into later life, the Ashcroft (2014) report found that while most service leavers smoothly transition to civilian life a lack of housing, finance, employment and lack of community were concerns around dealing with civilian life. Some participants in this study said that they felt civilian employers would not employ them. According to Ahern et al. (2015), they have a disconnection from civilians, a lack of purpose in civilian life, and a lack of purpose-connected feelings, contributing to a significant communal effort, deserved recognition, and appropriate management of mental health problems.

In addition to issues surrounding transition the veteran community, in recent years has felt the need to turn to activism and protest to have their voice heard as they feel they are being discriminated against with a hunt to prosecute veterans who served in conflict zones. The newspaper articles of Dixon (2018) and Scarlett (2020) describing attempted prosecution for alleged historical crimes committed during the Northern Ireland conflict whilst an amnesty for terrorist groups has been put in place is an example of this.

Veteran Physical and mental health

One obvious issue facing military personnel is that of physical injury incurred whilst serving and the recovery and rehabilitation process that the individual has to undergo. While some make a recovery that allows them to continue to serve some do not make this recovery and the injuries sustained will cause them to be medically discharged from the services. The psychological impact of encountering this kind of trauma, either as a victim of the event or as a witness to it can also lead the individual to suffer from mental health conditions. The House of Commons briefing paper, Mental Health Statistics for England (Baker 2018) gives a breakdown of the prevalence of mental health conditions into regions, gender, occupation and ethnicity but does not mention veterans as a community. NHS (2016) states that ‘one in four adults experience at least one diagnosable mental health problem in any given year, this equals 25% of the population, including veterans.

One such condition is post-traumatic stress (PTS) and according to APA (2022), it is categorised under Traumatic and Stressor Related Disorders in The Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). According to Yehuda et al. (2015), PTS is a condition that can develop following exposure to extremely traumatic events such as interpersonal violence, combat, life-threatening incidents or natural disasters. It can also develop from indirect exposure to the grotesque effects of war as first responders to serious injury or death and military personnel collecting human remains (APA, 2022). Its core features are the persistence of intense, distressing, and fearfully avoided reactions to reminders of the triggering event, alteration of mood and cognition, a pervasive sense of imminent threat, disturbed sleep and hypervigilance (Shalev, 2017). Yehuda et al. (2015) describe the symptoms as intrusive distressing memories, nightmares of the trauma, enhanced threat sensitivity and preoccupation with the potential for danger, difficulty sleeping, poor concentration and emotional withdrawal.

To be diagnosed with PTS, the sufferer must show symptoms that occur for at least a month and result in functional impairment or clinically significant distress (Adler & Hoge, 2008). PTS can be categorised into two types, it is termed ‘acute’ if symptoms last for less than three months and termed ‘chronic’ if persisting for more than three months (Javidi & Yadollahie, 2012). Shalev (2017) explains that the symptoms of PTS frequently present shortly after the traumatic event but a delayed onset seen in military personnel accounts for 25% of chronic cases. Delayed onset occurs at least six months after the traumatic event (Javidi & Yadollahie, 2012). For a diagnosis of PTS to be given an individual must present with multiple symptoms from a range of seven symptom clusters given in DSM. The DSM is now in its fifth edition (DSM-V) since its creation and according to Shalev (2017), there is only a 55% overlap between those identified as having PTS in the previous DSM – IV version. This indicates that 45% of those that were diagnosed with PTS following the DSM – IV guidelines would not have been diagnosed under DSM – V. Many studies that show statistics of the prevalence of PTS were conducted before DSM – V.

Various sources claim different statistics for the prevalence of PTS in the armed forces, according to (Shalev, 2017) 78% of those who experience combat will not develop PTS but the intensity of the event and the number of traumatic events that someone is exposed to will increase the likelihood of PTS developing. The APA (2022) however states that the rates of PTS are higher among veterans. The highest rates range from one-third to more than half are found in rape survivors, military combat and captivity and ethnically or politically motivated genocide (p 308). Many veterans support charities such as Combatstress (2019) use the figures from the Stevelink et al. (2018) study stating that the prevalence of PTS was lower in serving personnel at 4.8% compared to the 7.4% in UK veterans, this leaves the overall PTS rates for the military community at 6.2%. Zoteyeva et al. (2016) agree, citing Iverson et. al. (2009) that the rate of probable PTS from recent conflicts was 6.2% which is elevated compared to 4% of the general population.

Aside from PTS alcohol misuse and common mental disorders (CMD) continue to be the most common mental health problems the military and veteran community face with rates of alcohol misuse at 10%, and 21% suffering from CMD (Stevelink et al., 2018). The symptoms that the varied range of conditions present include anxiety, depression, negative thoughts, low self-esteem, anger, irritability, mood problems, and insomnia, these result in sufferers withdrawing socially and avoiding social situations. These can affect family and work relationships and an unwillingness to socialise. Hunt et al. (2014) conclude that ‘UK studies of military personnel suggest that their rates of common mental disorder are comparable to or higher than the UK general population, that military exposures do not seem to influence rates of common mental disorders and that certain groups of the military are far more likely to suffer from psychological distress rather than PTS, with a suggestion that general aspects of daily work seem to have a greater impact on common mental disorders that any specific exposure (p7).’ NHS (2016) rates of mental health problems amongst serving personnel and recent veterans appear to be broadly similar to the UK population but, working-age veterans are more likely to report suffering from depression.

Zoteyeva et al. (2016) observed that despite the high prevalence of mental illness in the population, not all veterans seek professional treatment (p308). It is acknowledged that mental health issues in the defence forces often exist within a culture of stigmatisation with servicemen often reluctant to admit to having a problem (Balfour 2018). This reluctance of veterans to come forward and seek help could be one factor that complicates the statistics. In the survey conducted for NHS (2016) 77.1% agreed to the question ‘I felt no one would understand my armed forces’ experience.’ With one comment that’ Non-military civilians do not understand military life and conditions and therefore veterans will always be wary of dealing with such people.’ 78.3% of veterans surveyed agreed to the question ‘I found it hard to ask for help for my mental health condition.’ One commented, ‘Servicemen are always trained not to show weakness,’ while another stated, ‘I knew there was help available, but a mix of pride and fear stopped me from asking for help.’ These attitudes often delay individuals’ from seeking help. Delayed onset PTS is 33% more common in veterans than compared to the civilian population (Andrews et al., 2009), and the finding by the charity Combat Stress is that the average delay between symptom onset and presentation to support services is 13 years (Iversen & Greenberg, 2009). This delay in symptoms and the unwillingness of veterans to come forward to ask for help with their problems may be leaving many veterans with undiagnosed conditions.

One personal way to cope with these issues that veterans face is to the mindfulness approach of the five steps to wellbeing 1) connect with other people, 2) be active, 3) learn new skills, 4) give to others and 5) take notice and pay attention to the present moment.

veteran Support agencies

To support military personnel in transition to civilian life The army has produced a series of information leaflets titled Transition to Civilian life (Army, 2022) to give guidance on transition and all three services provide resettlement training to help the transition. In recognition of the problems that veterans face there are now many support agencies created to cater specifically for the needs of service veterans. The main and largest of these include:

| Sailors Army Air Force Association (SAAFA) | https://www.ssafa.org.uk |

| Army / Navy / RAF Benevolent Funds | https://soldierscharity.org/ https://www.rnbt.org.uk/ https://www.rafbf.org/ |

| Royal British Legion (RBL) | https://www.britishlegion.org.uk/ |

| Combat Stress | https://combatstress.org.uk/ |

| Help for Hero’s | https://www.helpforheroes.org.uk/ |

| Forces in Mind Trust | https://www.fim-trust.org/ |

| Veterans and Families Research Hub | https://www.vfrhub.com/ |

| The Veterans Foundation | https://www.veteransfoundation.org.uk |

There is also The Confederation of Service Charities (Cobeso) which works to bring these charities together to collaborate to provide the best level of support to beneficiaries (Cobesco, 2022).

In 2011 the UK government recognised there was more that could be done to support veterans that had served their country and created the Armed Forces Covenant (AFC, 2022). It pledges to ensure that those who have served are respected, supported and treated fairly. Support is provided in several areas and ranges from education, career advice, financial assistance and access to health care in collaboration with the MOD, NHS and supporting charities. More than 2500 businesses have signed up and pledged support for the covenant and local authorities employ covenant officers to promote and monitor its implementation. The covenant was enshrined in law as part of the Armed Forces Act 2021 which obliges councils to comply with the principle of the covenant (LGA, 2022).

Most units will have their own associations that hold charitable status and hold veterans as lifetime members. These associations organise reunions for veterans to come together they often have local branches so veterans can come together locally. This can be seen in the RAPTC Constitution and the Duke of Wellington's Regiment Association Facebook page. Veterans also support themselves in organising reunions and social media events on sites such as the Facebook pages I served as a British Soldier and We Walked the Walk.

Music and veterans research

The various music projects are been highlighted in this research demonstrate the sparsity of research and music projects involving UK veterans and although there are many support groups for veterans such as the RBL Bravo 22 company, the Drive Project/BLESMA Limbless Veterans Organisation, and the Soldier’s Arts Academy, that have undertaken some arts-based projects with veterans and studies such as that have included veterans and drama such as that by Ackley and Wilson-Menzfeld (2021), there is little to find when looking specifically at music-based support projects with veterans. At the Forces in Mind Trust, Research conference in March 2022, where presenters from all parts of the UK shared the research and projects that were being conducted in their region there were reports of intervention projects and research including reading groups, clay modelling groups, Lego modelling groups and horticulture groups, no presenters were reporting on any music projects taking place. So, what research has taken place involving music and veterans? In the main, the research has been undertaken in other counties and has been mainly conducted with the focus on the treatment of PTS symptoms using music therapy.

Bensimon et al. (2012) conducted a study involving soldiers from the Israeli defence force that had experienced trauma and were diagnosed with suffering chronic PTS. The soldiers participated in a sixteen-week program where they took part in active music-making activities in group sessions. The programme was split into phases including improvising the trauma, where the participants were encouraged to talk about how the various sounds made by the played instruments made them feel and how this related to their trauma. Drumming out the rage session with drums was used to let out frustrations. Group discussions were held at the end of each session. The sessions were recorded on video and analysed by independent researchers. The participants also took part in an in-depth interview at the end of the program. The study found that all felt that they talk less about their trauma and more about general things, they felt an improvement in well-being and increased feelings of belonging. All gave positive feedback about the group sessions and their positive effect on their daily lives and that these improvements could not be made by just talking. (Bensimon et al., 2012.

The Bronson et al. (2018) review of Music Therapy Treatment of Active Duty Military examined four programs that included group music sessions, songwriting, improvisation, and performance with US military personnel, aimed at reconnection with the sense of self and increased socialization. The programs were conducted at different facilities, the main location being The National Intrepid Centre of Excellence (NICoE). One facility ran group sessions where they worked in groups of 4-6 members and received 1 x 90 min session of therapy per week for four weeks including week 1, music and movement, week 2, pleasant & unpleasant sounds, week 3, song wring / jam session, week 4, improvisation. At another facility group and individual sessions targeted goals specified by patients. Working in 5 per group they also had 1 x 90 min session for 4 weeks with a different focus each week: week 1, music listening, week 2, active music making, week 3, music for relaxation, and week 4, songwriting. The review also describes a creative arts café, a performing arts venue that patients and staff can access to share creative expression allowing patients to grow in their recovery process and is used as the first step for creative engagement outside of therapy sessions. The evaluation of the sessions was through the number of participants returning for follow-up sessions with an uptake of 79%.

Bradt et al. (2019) conducted a retrospective analysis of fourteen songs created by military service members while in therapy at NICoE and claims to be the first study to examine the therapeutic benefits of songwriting in a military population. The 14 songs were written by 11 service members over 2-3 individual music therapy sessions. The lyrics of the songs created four main themes, personal struggles, barriers to recovery, moving forward, relational challenges and positive relationships and support. The lyrics expressed positivity and resilience despite the individual's struggles. The study found that in veterans, collaborative songwriting can address, shame, depression, social isolation, and difficulty communicating along with the questions revolving around Identities - who was I? who am I now? Abilities - what can I do now? And survival guilt - why am I still here? (Bradt et al., 2019).

Balfour (2018) describes two projects with Australian military communities, one with serving members in Afghanistan in 2013 called ‘Going Home’ this was a part of a larger project focused on supporting ex-military and their families through arts-based projects, where a song and video were produced to aid a veteran’s charity. The song was written by a diplomat and songwriter who wrote the song over four months while working at a military base in Afghanistan. The song was based on the conversations and observations with the personnel at the base. The song was performed at the base and released on Youtube and to date, it has had 61,200 views. Another project Balfour (2018) describes is ‘The Soldiers Wife’ and it involved widows of ex-servicemen in aid of their veteran’s widows ‘Laurel Club’. In this project, a team of songwriters visited the widows club to talk to and engage with the veteran's widows to gain material to write songs to create a CD that could be sold, and the proceeds go to the club. The team found it difficult at first and it took eight weeks for the club members to engage effectively. A CD was eventually produced, and a second volume has been released.

Dhokai (2020) describes a project to engage US military veterans through guitar workshops. This was decided by interviewing veterans to investigate the kind of music that they would engage in. The focus of the guitar workshops was to re-engage or maintain a lasting connection to music. The program started with 20 participants in the workshop for a 10-week series. Due to varying skill levels, a levelled learning approach was used where the individual could choose the difficulty of their approach, one could play a simpler version of a chord while another may play a complex version. This allowed the group to work on the same music at different levels. In the second series of workshops level, 1 and level 2 ability groups were created and a framework and format for the workshop series were developed. They ensured that the music was meaningful through pre-session surveys and encouraged peer mentoring and conversations outside of sessions this meant culturally the workshops allowed the veterans to engage in personally meaningful music. A sense of camaraderie was developed through casual conversations and interaction between group members. Peer support and mentoring were encouraged, and inclusion and collaboration were important learning goals. Continued communication was weekly emails to members to update practice at home. Surveys were given to participants at the end of each 10-week series and the project resulted in increased social interactions and social connectedness, interest in learning new skills, better family relationships, decreased social isolation and an increased feeling of wellbeing (Dhokai, 2020).

In the study carried out by Zoteyeva et al. (2016) with Australian veterans to explore how music is used to manage symptoms of depression and stress and the links between the prevalence of mental health symptoms and veterans’ music listening patterns. From the group of 233 surveyed almost two-thirds were likely to have a mental health problem. The study found that participants engaged with music more than any other leisure activity. A prominent strategy was listening to music when predicting negative social interactions and depression. The findings were that those veterans experiencing high levels of depression, stress and negative social interactions use music to regulate their emotions and that they may be using their musical identities to self-medicate in a proactive way to prevent the build-up of emotional distress. (Zoteyeva et al., 2016).

Research from studies involving civilians can be used to further inform the benefits of music and the treatment of mental health problems. In the review of the potential effects of collaborative songwriting in civilians with PTS, Noyes and Schlesinger (2017) conclude that the writing of lyrics was a cathartic process for the participants, the process produced a strong sense of community and that the programs reduced PTS symptoms. In the Review of Music Therapy for PTS in adults, Landis-Shack et al. (2017) found that there was increased group cohesion, self-esteem and feelings of self-worth and decreased social isolation and feelings of worthlessness in programs including group music therapy sessions, instrument tuition, improvisation, songwriting and recording. In a study involving displaced families due to armed conflict in Columbia that had had their social place and personal identities affected by the displacement, Rodríguez-Sánchez and Cabedo-Mas (2020) describe how eight families took part in a Music for Reconciliation program for over a year. The participants received recognition for having developed an important skill, this gave them a positive appreciation of themselves. It gave them increased confidence in their own music-making and music became a salient and prominent identity. The program had a positive impact on their social place, social status, and an increased sense of belonging.

Music Interventions

Music Therapy:

All but one of the research projects highlighted have been conducted by or the sessions led by Music Therapists. The American Music Therapy Association (1999) cited by Green (2011) defines music therapy as the ‘clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions […] within a therapeutic relationship to address physical, emotional, cognitive and social needs of individuals. Bunt (1984) cited by Stige and Aaro (2012) explains that ‘much of the early work of the professional music therapist began in the large institutions for the mentally handicapped and mentally ill people (p 44). This lead McFerren (2010) to describe ‘the traditional music therapy practice as an intervention for unwell clients. (p 29).

The therapist will use a medical model to assess the needs of the individual and select an appropriate course of treatment that will have a positive effect on the assessed needs. The patient’s pathology and clinical diagnosis strictly define the aims, means and outcomes of the treatment. Effectiveness is determined according to a change in symptoms (Wood & Ansdell, 2018). Green (2011) describes how, when treating trauma survivors, the therapist creates a safe space to explore the meanings of the traumatic memories the trauma victim has and cites Cohilic, Lougheed and Cadell (2009) stating that it is widely excepted that, to recover from PTS or trauma, individuals must gain access to their traumatic memories so they can re-examine, modify and reconstruct them. Green (2011) explains that when someone is musically engaged with the therapist the emotional impact of the traumatic experience becomes accessible and that once those memories have been reconstructed the individual can face the task of creating a future identity and not be defined by the traumatic event.

To suit the clinical need the therapist can draw upon a range of intervention activities these could include: singing, musical improvisation, listening exercises, and a discussion of the emotions conveyed through a piece of music heard by the patient (Bond & Wigram 2002) cited by Landis-Shack et al. (2017) Although traditionally therapy is on an individual basis, Landis-Shack et al. (2017) also describe the use of group work, playing in bands, recording music and songwriting. Bensimon et al. (2012) also describe the use of group work with improvisation, drumming and listening to relaxing music.

Since the late 1990s, some Music Therapists have been adopting a more community-based approach rather than the ridged traditional approach. This has been termed Community Music Therapy and has been discussed by Pavlicevic and Ansdell (2004), Ansdell and DeNora (2012), Ruud (2012), and more recently by Ansdell and Stige (2015). Music Therapy achieved state registration in the UK in 1996 and is now classified as Allied Health Professionals by the Health and Care Professions Council (Wood & Ansdell, 2018). Mental health providers must refer clients to music therapists if they want to incorporate music therapy into the treatment (Landis-Shack et al., 2017).

Community Music:

In contrast to the academic, medical profession that is traditional music therapy Community Music traces its roots to the cultural radicalism of the community arts movement. Higgins (2012) describes CM as an expression of cultural democracy where the musicians create musical opportunities for a wide range of cultural groups and as having three broad perspectives:

1) Music of a community.

2) Communal music making.

3) An active intervention between a music leader or facilitator and participants.

It is, in essence, about widening the participation of music in the community rather than those with clinical needs. Community musicians seek to enable accessible music-making opportunities for members of the community (Higgins, 2012) and are committed to the idea that everybody has the right to and ability to make, create and enjoy their own music. Kelly (1984) states that Community Arts began as one strand of activism among many during the late 1960s. Veblen (2008) cites Cole (1999) and describes the theme of ‘access to arts for all’ that emerged in the 1960s and 1970, and the links between the term ‘Community Music.’ The early manifestations of Community Arts were associated with the working class and working-class values. There was opposition to what was seen to be the ruling classes and its highbrow approach and control over the arts and what was unworthy. This caused growing political activism and radicalism. The theme of CM became political, activism and justice are at the core of CM (Higgins & Willingham, 2017). The core value is that music should be accessible to all and CM practice is built on the premise that everybody has the right and inherent ability to create and participate in the music (Higgins & Willingham, 2017). The continued distrust of cultural hierarchies and institutionalism would cause resistance to professionalise the practice of CM and state registration of Community Musicians.

By 1989 ‘Sound Sense’ was created as a national development agency, by 1990 the different areas of employment for Community Musicians were identified and the first training courses in the UK found momentum by 1994 and the term training rather than education was used to describe the professional development as vocational rather than academic (Higgins 2012). This training continued to develop with Higher Education establishments including CM in their courses and the introduction of postgraduate courses. The academic discussions surrounding CM continued and in 2008 the International Journal of Community Music was established (Higgins 2012) and ‘as a direct response to this wave of international interest, the International Centre for Community Music (ICCM) was established (Bartleet & Higgins, 2018).

Higgins (2012) describes one perspective of community music as ‘an active intervention between a music leader or facilitator and participants.’ Deane and Mullen (2013) agree to cite Everitt (1997) that community music describes professional musicians carrying out interventions intended to have consequences other than musical (p26). Those that work this way do so with a commitment to a musical crucible for social transformations, emancipation, empowerment and cultural capital (Higgins & Willingham, 2017). The Community Musician achieves this by running Clubs, workshops, and community events taking music into the community.

Higgins (2012) bases the philosophy of community music on ‘acts of hospitality.’ This starts with the welcome of the participant to the group, the welcome is an invitation, an invitation to be included. This welcome although some may say is unconditional, there is an expectation that the new participant will actively take part in activities and that they understand this will be the case. The facilitators aim to provide a safe space that is built from trust and respect and friendship that evokes collective and inventive conversations that aim to encourage music making that is open, creative and accessible (Higgins 2012). Community musicians emphasize conversation, negotiation, collaboration and cultural democracy (Higgins & Willingham, 2017). The workshop is described as a democratic event where the participants are worked with rather than worked on and an element of responsibility exists (Higgins 2012).

‘Academic studies have backed up the common-sense notion that in all times, and in all cultures, music seems to have been closely associated with individual, social and spiritual healing’. (Gioia 2006; Gouk;2000; Horden 2006) citied by (Wood & Ansdell, 2018) . To extend this idea, in her TED Talk; ‘Community Music a Power for Change’, Nikki-Kate Hayes goes further than just widening participation and describes community music as being able to reduce street crime, raise standards in schools, speed up healing, slow down dementia, extend life, and save money for the NHS (TEDxTalks, 2017).

Community Musicians are also working in hospitals, care homes and prisons, many areas that were traditionally the domain of the Music Therapist. According to Wood and Ansdell (2018), this shift to working with other sociocultural enterprises and working with people with more overt pathologies began in the late 1990s. The diverse range of activities encountered by community musicians lead to this description by Kushner, Walker & Tarr (2001), cited by Deane and Mullen (2013):

Community musicians are boundary walkers [inhabiting public territories that lie between other professions. They take their music to health settings, schools, the voluntary sector, and the criminal justice system-and while denying they are therapists, teachers, community workers or probation officers, they find themselves working alongside these people and often doing what they do. (p4).

The guitar workshops for veterans in the US described earlier by Dhokai (2020) are a good example of CM in action. Other examples can be seen in Cohen and Henley (2018), ‘The Many Dimensions of Community Music in Prisons’. A key feature of this text is the concept of ‘possible selves’ they cite Markus and Nurius (1987) defining possible selves as representations of individual's ideas of what they might become, what they would like to become and what they are afraid of becoming and describe developing an identity as a transformative process. The relationship between the participant and the music facilitator has been found to be an important factor to develop social and personal agency and a context for a new social identity. The way that the facilitator welcomes the participant, and models positive musical and social behaviours help incarcerated people to feel normal (Cohen & Henley, 2018).

Birch (2020) provides another example of CM in prisons with Emerging Voices, a singing and songwriting project as part of the Prison Partnership Project between York St John University and HMP New Hal, a female prison. The program consists of weekly three-hour sessions at the prison. The principle of the welcome was maintained and although starting with 10 participants some left the project part way through, and others joined. Creating a safe space was paramount and reading the room required paying attention to body language and facial expressions to pre-empt emotional triggers and act accordingly. Standing in a circle gave a sense of equality and the women could share their music tastes and choices in the songs was important. Collaborative songwriting took place using inspirational quotes, words, and images as stimuli for ideas. Emerging themes from the project were 1). Improved emotional wellbeing, 2). Personal and creative skill development,3). Creation of positive social cohesion.

Unlike the music therapy model of re-visiting the trauma, the CM model does not focus on treating the trauma but recognises the potential for positive therapeutic outcomes in participatory music making such as healing, personal growth and positive social change. Birch (2021) describes how the prison partnership project discourages a focus on trauma-based narratives and avoids the triggering of traumatic memories while assuming that, as the figures suggest some of the group will be trauma survivors as the statistics suggest. Birch (2021) explains that with this in mind it is important that the mishandling of a potentially traumatic symptom due to misunderstanding or misinterpreting should be avoided. This can be done through education and training to be trauma-informed and understand what trauma is and its implications. The practitioner can then use a trauma-informed framework of safety, trustworthiness, choice, collaboration and empowerment in their practice.

Casestudy G4V-Wales

G4V is an American non-profit organisation dedicated to providing relief to struggling veterans through the healing power of music and the community (G4V, 2019). The organisation was started because the founder, Patrick Nettesheim, a guitar instructor, started working with a Vietnam veteran who found that guitar lessons were appropriate for veterans in allowing self-expression and positive human interaction. A G4V guitar instruction program was developed with the aim of providing struggling veterans with physical injuries, PTS and other emotional problems with a unique therapeutic alternative (G4V, 2019). G4V provide weekly individual lessons so that students can learn at their own pace and monthly group sessions to establish a community atmosphere. Once a student has completed the initial 10 lessons of the programme the student is awarded their own guitar to continue within the groups. In Dillingham (2011), a study with the US Department of Veterans Affairs carried out a 6-week program with 40 US veterans suffering from PTS. The veterans participated in one individual guitar lesson per week and one monthly group guitar session facilitated by experienced instructors in partnership with G4V. The veterans were aged between 22 and 76. According to Dillingham (2011), the results were remarkably successful, showing positive benefits for the 6-week intervention. The primary outcomes included a 21% improvement in PTS symptoms, a 27% reduction in symptoms of depression and a 37% increase in feelings of a better quality of life.

Casestudy NWVCoD

The NWVCoD was created as a Facebook page in October 2021 and a go fund me page was set up. A large donation was given by an injured veteran that enable the purchase of equipment and provide funds for the rental of a rehearsal room and the first in-person session was held on 2nd February 2022. Its formation was the idea of its founder who had served in the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers as an infantry soldier and drummer. The aim of the group according to their constitution is:

To form a non-profit organisation in a military-style Corps of Drums (CoD) to incorporate veterans, comrades, and the local community in the local area. The primary aim is to support the annual Remembrance Day parade as well as any locally (Northwest) organised public events.

Membership of the group is open to any person 18 or over located in the Northwest area who has a military background. Tom the organiser states:

‘We are open to all cap badges. Our overall aim is to play as a traditional infantry Corps of Drums but doing that seems to be helping our members mentally this is just by accident and hope this will carry on becoming a support network. We hope to be not just a Cops of Drums but also the “Go To” for Veterans around the Northwest.

The NWVCoD started rehearsing once a week in a rehearsal room in St Helens, Lancashire and the group play traditional military CoD music. They now also have a satellite group in Bolton. The group gave its first performance on 12 June 2022 on the birthday of the injured veteran that generously donated to their start-up fund. The music. Through fieldwork visits to the group and through observations, discussions and interviews with the group founders and members the following themes were identified. Upholding and Upkeep of TraditionsVeteran AttitudesIdentity Self-Esteem and SkillTrauma, Mental Health, Distraction & Diversion Inclusivity and Environment of Support (Hospitality)Commitment to the music Barriers to Operating/ Funding Issues

Upholding and Upkeep of Traditions:

The NWVCoD has the upkeep of traditions at its heart, the founding members come from a time when every infantry battalion had its own CoD with its own unique uniform and traditions, Tom tells us.

‘As I got to think about it I got to realise that a lot of the regiments are losing their Corps of Drums. I think that there is only something like 9 CoDs left in the British army now, so they are also losing all the small traditions particular to CoDs. We hope to keep as many of these traditions and stories alive for future generations. Now it seems as though we are hopefully going to become a source of the traditions of the regiments for people maybe in the fifties to right through to those people just getting out and times change, and traditions change and we are hoping to gather all those traditions together so some of them are saved.’

Graham informed us that he took up the bugle partly because it was hard to find someone to play the last post at a veteran’s funeral, a tradition that was slipping by.

Identity Self-Esteem and Skill:

A significant theme that emerges from the observations and conversations is the effect the group has on self-esteem and their concept of identity. Harry confided ‘it helps me remember fondly my days in the CoD. Also returning to something I am good at has helped my self-esteem and sense of identity that I had lost during my time out of the army.’ Dick tells us ‘I Joined the army & was in the CoD for my regiment. I left the Army but joined the Orange Order that had a marching band – that meant that I kept part of my military identity as a civilian. I was always known as “Dickie drums.’ Tom observes ‘Dick left the Army because of an injury and, the decision to leave was made for him through injury. In some ways he hasn’t left he's still doing it with us.’

Tom as the founder of the group even admits that the formation of the group was a selfish one, based on the pride he had in a skill that was being lost:

‘I think there has always been that need there and it's something I was always quite good at, I was leading tipper in the platoon, so I was the lead side drummer, so was always quite good at it. I’d sort of lost it a little bit and wanted to get it back basically.

Dick also confirms that pride in a skill is part of his identity as a veteran and tells us that being part of the group, ‘It has re-established the pride in my skill and identity – still good at something.’

A small number of the group, and although veterans did not have any prior musical experience. Taking up music with the group has now expanded their identity into a musical identity. Graham tells us:

‘I served in the army but was never in a CoD and didn’t play an instrument. During the lockdown, I bought a bugle and with online support and the sessions here I can now play. Being involved with other veterans is great and playing the bugle has given me a new identity.’

Veteran Attitudes:

The formation of military identity and the military identity legacy described by Cooper et al. (2017) continues after leaving service although stereotypical many veterans conform to certain attitudes & behaviours. The group members attitudes towards themselves and as a community compared to civilians seem to be typical of those described by Balfour (2018). When Tom was looking to find a CoD to play with after leaving the forces he said:

‘I looked at joining the Fusilier association Corps of Drums but got the impression that they weren’t really interested in having me there. I believe this is because they are all Civvies who have never served and didn’t want me upsetting the status quo.’

Others also had problems adjusting to working with civilians playing military music Dick told us:

‘I was injured in Iraq and medically discharged. I tried to start a CoD in my local area and had the support of an association, but they did not understand the military element of the music and it didn’t work out.’

The general stereotypical feeling that veterans have toward other veterans is also demonstrated by the group. Tom explains: ‘We can't make someone a vet, but we can teach a vet to play the drum or a flute and because he’s a veteran he would fit right in. They are of the same mind as us anyway, aren’t they? He goes on.., I believe that any of our members will tell you that just being in the presence of like-minded people helps with their mental health immensely. I know of no Veteran that classes him or herself as a Civilian. In the veteran world, there is also a resistance to civilians who claim to have served but have not, there is a suspicion felt when things don’t seem quite right. Tom describes one situation:

‘We did have a guy that turned up who we think had mental health problems and he left of his own accord, but we didn’t make him feel entirely welcome but none of us believed he was actually a veteran. He had the stories; he knew the people, but things just didn’t add up. None of us persecuted him or gave him a hard time, in fact, he left himself.’

Trauma, Mental Health, Distraction & Diversion:

It is reasonable to say that just as with any group that is brought together, some in the group will suffer from mental health problems. Regarding the NWVCoD, Tom tells us: ‘We do have Veterans that have suffered Trauma and I believe that every Veteran that finished training and served in his unit suffered trauma when they were released from service and abandoned to Civvy Street with no support.’

With one another the group can share their mental health problems, Harry was comfortable enough to disclose that he suffers from PTS and is having continuing psychiatric treatment. He was also open to discussing his triggers and due to PTS triggers, he did not want to do video interviews. He was happy to take part with the camera running background, but no face-to-face interview on camera.

Joe was also quite open and explained how being in the group was helping: ‘I have been in a lot of trouble at work recently and suffer from depression and anxiety. Being in the group has helped me cope and feel happier in life.’

The group is also a good diversion and distraction away from stressors and mental health problems for many of the group. On observing Brian who has problems & stress, in life at work. He arrives at the session looking worried and his shoulders dropped. Once the session starts, he looks younger fitter and happier while playing. Harry comments that when he is in the room with the group for rehearsal, he can forget everything outside of the room for 2 hrs and Tom describes two other members that benefited from the diversion and distraction that participating provided:

‘When he was there, he was relaxed and enjoyed himself and we also found out by chatting to him that he hardly ever left his house. We have another guy who does a lot of fostering and stuff and when he comes to us, he’s away from all that and all the stress and hassle and he’s back to where he was when serving.’ For some, diversion and distraction can also be found in individual practice when preparing for rehearsals.

Graham explains: ‘I have PTS, the group helps me to focus on positive things and I can also pick up my bugle and practice at home when I’m not feeling great.’

Inclusivity and Environment of Support (Hospitality):

The group focus on inclusiveness and support that is restricted to the military veteran community, within this the group are very welcoming to any veteran that shows an interest in the group and encourages those with or without musical backgrounds to join in. Tom explains:

‘If someone is interested and wants to do it we are quite willing to teach them to play the flute or play the drum.’ Some of our members don’t have a social life and have lost touch with their Veteran friends. We give them that back. With one veteran who left, we talked him into coming back we put him on the club committee and he’s fantastic and we think he would have gone back home, sat at home, and done nothing again.’

In rehearsals the sessions start relaxed with no pressure, group members arrive, greet each other, and swap light-hearted banter. Joe says: ‘I have enjoyed meeting people of similar interest and enjoy the banter without being offended.’ They then start to warm up individually, left to their own devices & thoughts and come together with the rest of the group when ready. The leader waits for them to come together and be ready before making a start. The band practices sitting down as a static band rather than marching so those who are injured can still take part. In the first session observed they played one piece all the way through, then discussed each other’s roles having a very supportive & respectful discussion. The second piece was more upbeat with a faster tempo. At end of the piece, there was more military banter. One participant has an ongoing illness he plays the flute and keeps up with others most of the time, he stops where he needs to and picks up again in an appropriate place in the music and everyone accommodates this. Any mistakes made were tolerated with humour. On one piece where Dick was struggling Billy & Ben reassured him ‘You are doing all right- you're really doing all right.’ Later Dick commented, I enjoy the no-pressure banter and the supportive environment.

Commitment to the music:

Although Dave commented ‘We are veterans, we are not expected to be top-notch CoD, we are just having a go, doing gigs and turning up and we are getting better,’ and through all the support and mindfulness of wellbeing there is also a commitment to the music and desire to be taken seriously by the military music community. In the subsequent sessions observed the sessions were different and they ran through a set in real time for the rehearsal for the performance on 11 June. The drummers concentrate but watch each other & keeping time together. Side drummers in flow.

There was a discussion at end of the set highlighting mistakes and corrections all views were taken respectfully. The format of the sessions was different and varied according to need with the drums and flutes moving to different rooms to practice their parts. Billy was coaching & mentoring the other two flautists in a supportive, respectful, and friendly manner. The two were respectful and listened to his coaching. At the tea break halfway through the rehearsal, there was more military banter and throughout the session, the banter was displayed at appropriate times and did not interfere with the music making. After the break was a run through the whole set with no discussion until the set was complete. Again, a discussion was at the end of the set highlighting mistakes and corrections all views were taken respectfully and areas to work on at home were taken away. This was the build-up to their first performance on the birthday of the disabled veteran that had donated to the group. The build-up to the performance was taken very serious by everyone demonstrating not only the supportive side of the group but also their serious commitment to the music.

Funding Issues / Barriers to Operating:

Money or lack of it was a big obstacle to the set-up of the group and could not have happened without a large donation to help them set up. Rehearsal space has been provided by a local brass band at a reduced rate in sympathy with the group's cause. According to Tom, the group is ticking along, but money is still a big issue. Recruitment is also another concern and although the Facebook group has 269 active participants have plateaued at a core consistent group of 8-10 players. The group are optimistic about its future, that the project will grow, and music is an important tool to use in promoting wellbeing in the veteran community, Tom concludes:‘I think what we are doing is what the breakfast clubs set out to do, that doesn’t seem to quite able to do it, breakfast club – fantastic idea – bring people together, but I think because we've got the music as well, we've got that interest on top that’s what gels everyone together the music is the glue that sticks it all together.’

Discussion and Future Directions

The veteran population qualifies as a community through their shared military identity and the bonds created by the common military culture is, according to Lancaster et al. (2018) so strong that military personnel view their comrades as family. This continues after service within the military legacy described by Cooper et al. (2017). One veteran interviewed for this study stated that he did not know of any veteran that would ever call themselves a civilian. This insider/outsider view has been strengthened by the activism and protests of the veteran community to the extent that the government created the Armed Forces Covenant in 2011 and the creation of the appointment of Johnny Mercer MP as Minister for Veterans Affairs in 2022. A veteran himself he was driven into politics by his displeasure at how his cohort of military personnel and veterans had been treated by the government (GOV.UK, 2022). The Armed Forces Covenant was made law by its inclusion in the Armed Forces Act 2021. The veteran population is also a significant community at 2.8 million, 4.4% of the population of Great Britain (RBL, 2014).

According to Iversen and Greenberg (2009), the limited existing evidence suggests that the majority do well after leaving the armed forces, and as previously stated the RLB household survey of 2014 findings were that PTS, mental health problems, homelessness, prison populations and suicide rates amongst veterans were comparable to the general population, however, Cooper et. al. (2017) describes the military culture as biased by hegemonic masculinity where qualities of emotional toughness aggression and self-reliance are promoted and dependence, displaying emotion and weakness are frowned upon. Mental health issues in the defence forces often exist within a culture of stigmatization with servicemen often reluctant to admit having a problem (Balfour 2018) and it has been identified that for various reasons some veterans do not seek help. The diagnosis of mental health conditions is also constantly evolving, and it is now more unlikely to be diagnosed with PTS for example due to the changing diagnostic criteria Shalev (2017) that is only a 55% overlap in diagnosis under DSM-V compared with DSM-IV this will affect whether an individual qualifies for treatment. Authors also quote different statistics from different studies and this, combined with evolving diagnosis criteria and veterans not coming forward for help contributes to making mental health statistics complex, confusing and possibly unreliable. While the MoD uses gaining employment as a key measure of successful transition (Ashcroft, 2014), Cooper et. al. (2017) cite Jolly (1996) and acknowledge gaining employment does not necessarily indicate a good transition back into civilian life. One could argue then, that, having a job and not having a diagnosis of a mental health condition does not necessarily mean that the veteran is living a fulfilling life, coping, and doing well. Soon, the demographic of the veteran community is also set to change drastically by a reduction of one million by 2028 (MOD 2019). This will be almost a one-third reduction from the RLB (2014) survey. This will result in an increase in veterans working to 44% compared to the previous 38% (MOD 2019). These sudden changes in statistics will cause the RLB and other studies' findings irrelevant while research catches up. In effect, the community will quickly get smaller but younger where increased support may be required and projects such as CM interventions become more appropriate.

Just because there is a lack of empirical evidence to support the notion that community music projects can be of value to the UK veteran community it should not result in the notion being discounted. There is evidence through Bensimon et al. (2012) and Bronson et al. (2018) that group music making is valuable within wider treatment protocols in with Israeli and US military suffering from PTS. Bradt et al. (2019), Specifically investigated the value of songwriting with US veterans and found positive results in reducing the symptoms of mental health conditions. Noyes and Schlesinger (2017) observed similar results in civilians using songwriting as therapy for PTS. Although these studies were conducted by music therapists, group music-making and collaboration in these studies fall clearly within the community musician’s boundary walker remit. Groups created by community musicians to work with the veteran population can give access to the wellbeing-promoting effects of collaborative music making to those who do not qualify for medical referral of self-diagnose, and also provide continuity and extended support for those whose prescribed treatment has ended.